Richard Matheson’s The Shrinking Man: Size Matters

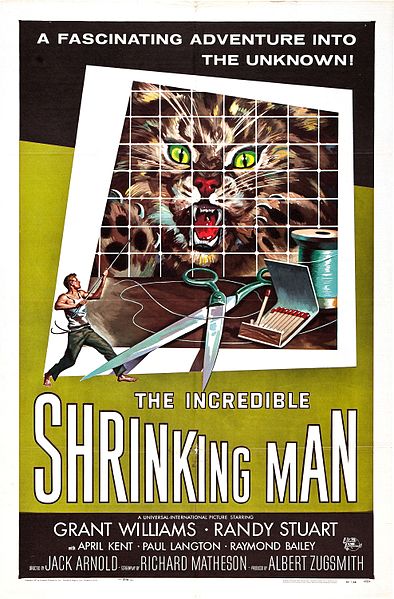

This is an analysis of one of my favorite SF novels. I originally presented this at a Popular Culture conference a few years back. A friend suggested I publish at the time, but the hoops associated with academic publishing were not the ones I wanted to jump through back then. Now I make my own hoops and jump through them at will. If you haven’t read Matheson’s The Shrinking Man, you should pick up a copy; it’s a well-crafted work, and I really think Matheson is under-rated. Like Philip Dick and others, he was writing some pretty sophisticated and thoughtful stuff disguised as pulpy newsstand fare. I can just imagine someone picking this book off a dime store paperback rack in 1956 and getting more than they bargained for.

There are some spoilers in here, but not major ones.

Size Matters: Emasculation in Richard Matheson’s The Shrinking Man

On its surface, Richard Matheson’s 1956 novel The Shrinking Man is about the perils of protagonist Scott Carey as he grows smaller day by day after exposure to radiation. On a deeper level, however, Carey’s plight revolves around and symbolizes anxieties over emasculation. Carey shrinks not only literally but figuratively, undermining his gendered identity as husband, father and provider. Calling into question Carey’s sense of masculine adequacy prior to his literal shrinkage, the novel suggests that anxieties over masculinity and emasculation are a function not only of the freak accidents of science fiction but also of mainstream 1950s American culture and the exigencies it forces upon the “typical” male. Carey’s accident and loss of stature merely magnify his existing insecurities and failure to “measure up” to standards of masculinity. The text clearly has misogynistic elements, namely the scapegoating of Carey’s wife and her association with the black widow that torments him, but at the same time Carey’s association of male sexuality with power and dominance can be read as critical of the hyper-masculine response to threatened emasculation. Carey’s eventual triumph over his surroundings and anxieties appears to be a celebration of masculinity—a message the text clearly sends—but since the text also suggests that such triumph may only be had through a return to the primitive, Carey’s victory may be read as a hollow one that limits masculine subjectivity, presenting a dichotomy between emasculation and hyper-masculinity that cannot be negotiated.

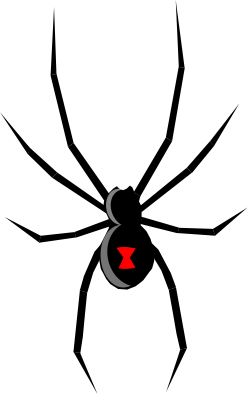

The basic plot of the novel mirrors the 1957 film adaptation, which Matheson also wrote and with which many are more familiar. Scott Carey, husband and father, begins to shrink one seventh of an inch each day after exposure to a combination of radiation and insecticide. As he grows smaller, he grows increasingly anxious not only about his condition but also about his ability to provide for his family. After a series of humiliations, Carey is eventually trapped in his basement, presumed dead by his wife, and must make his way alone in an increasingly hostile and gigantic world. His nemesis in the basement is a black widow spider which hunts and torments him and which he finally determines to kill even as he comes to realize he will soon only be two sevenths of an inch tall, then one seventh, and then—Carey assumes he will simply vanish. Rather than succumb to his environment or his thoughts of suicide, Carey thus clings to the masculine trope of hunter/gatherer, taking comfort in action rather than passivity, and is finally rewarded with a version of survival that he had not expected.

The basic plot of the novel mirrors the 1957 film adaptation, which Matheson also wrote and with which many are more familiar. Scott Carey, husband and father, begins to shrink one seventh of an inch each day after exposure to a combination of radiation and insecticide. As he grows smaller, he grows increasingly anxious not only about his condition but also about his ability to provide for his family. After a series of humiliations, Carey is eventually trapped in his basement, presumed dead by his wife, and must make his way alone in an increasingly hostile and gigantic world. His nemesis in the basement is a black widow spider which hunts and torments him and which he finally determines to kill even as he comes to realize he will soon only be two sevenths of an inch tall, then one seventh, and then—Carey assumes he will simply vanish. Rather than succumb to his environment or his thoughts of suicide, Carey thus clings to the masculine trope of hunter/gatherer, taking comfort in action rather than passivity, and is finally rewarded with a version of survival that he had not expected.

An aspect of the plot barely acknowledged in the film but developed at length in the novel is Carey’s increasing sexual frustration. With a man’s mind and libido trapped in a body that increasingly resembles a boy’s, Carey begins to question his sexual adequacy and desirability while the decreasing frequency and ultimate cessation of intercourse brings about an identity crisis, suggesting an integral link between sexuality and masculine identity. At 49 inches tall, he attempts to initiate sex with his wife, Louise, but finds himself “terribly conscious of his size” and asks himself if Louise is “talking to him as if he were a boy.” Feeling “devoid of masculinity,” he stares at “the flesh-walled valley between her breasts” and considers himself a boy: “indecisive, withdrawn, much as though he’d conceived the ridiculous notion that he could somehow arouse the physical desire of this full-grown woman.” When finally he succeeds at arousing his wife’s desire—and not just her pity, as he has feared—he sleeps, contented and temporarily able to forget his plight.

The theme of sexual intercourse as denial of emasculation repeats throughout the text and intensifies the smaller Carey gets. The satisfaction of sleeping with his wife once more is temporary and unlikely to be found again as he shrinks further. By the time he is 35 inches tall, he finds himself watching Louise undress at night “as if he were a man dying of thirst looking at unreachable waters.” And at a height of 18 inches, he becomes so desperate that he seeks another woman—Clarice, a sideshow performer billed as Mrs. Tom Thumb whose height is approximately the same as Carey’s. Embracing Clarice, Carey equates manhood with female contact: “Just to be a man again. To hold you like this.” Just as sex with Louise brought a temporary halt to his feelings of emasculation, so does a night with Clarice renew his belief in his masculinity. Clarice offers direct reassurance, telling him “You’re a man,” a phrase he ponders all night long. He realizes he has forgotten that he is still a man, and Clarice’s presence restores him, as he thinks: “A man’s self-estimation was, in the end, a matter of relativity. Here he lay in a bed in which he was full size and there was a woman held in his arms. It made all the difference.”

However, the pattern repeats with Carey’s continued diminution, and the impulse to sleep with a woman as a means of solace reaches an absurd level when, small enough to now be living in a doll house, Carey spends the night with an actual doll given to him by his 5 year old daughter. Desperately lonely after having recently stopped wearing his wedding ring on a string around his neck, and realizing that taking it off has “formally ended” his marriage, he carries on a conversation with the doll, telling it his life story before laying it in his bed and wrapping his arms around it to spend the night. The doll is both sexualized and sterile: “She sat there stiffly, legs spread apart, arms half raised, as though she contemplated a possible embrace.” Carey informs the doll that she is “flat-chested” and has celluloid eyelashes before apologizing for being rude. Getting no reassurances of his masculinity as he did with Louise and Clarice, Carey manages to fall asleep next to the doll but wakes in the night and stares “dazedly at the smooth, naked back beside him, the yellow hair tied with a red ribbon. ‘Who are you?’ he whispered. Then he touched her hard, cool flesh and remembered. A sob broke in his chest. ‘Why aren’t you real?’ he asked.” Having reached a point where female companionship has become a complete impossibility, and having conflated masculinity with heterosexual intercourse, Carey is without any means of affirming his masculinity. Not long after this encounter with the doll, he finds himself in the basement confronted by a new challenge to his manhood, a black widow spider which can be read both misogyni stically and as a symbol of the sexual dynamic with which he has struggled throughout the text.

stically and as a symbol of the sexual dynamic with which he has struggled throughout the text.

That Louise is associated at least partly with the spider seems relatively clear. An early description of the spider focuses on its unsavory mating practices: “Black widow. Men called it that because the female destroyed and ate the male, if she got the chance, after one mating act.” While Louise certainly does not kill her mate, she is portrayed in a less than sympathetic light. The very first sentence in which Louise is introduced in the texts reads: “When he told her, the first thing she did was laugh.” The subject of her amusement is, of course, the absurd notion that her husband is shrinking, and that she would laugh at the idea suggests not only a natural reaction to such absurdity but also a cold, unsympathetic, belittling and emasculating response. This initial opposition between Carey’s need for sympathy, companionship and affirmation and his wife’s incredulity sets the tone for her further characterization. While she later does respond with sympathy, it is often tempered with impatience and frustration, as when she tells her diminutive husband to “stop squeaking” at her during one of his tirades. Growing sexually and emotionally distant from him, she inadvertently heightens his feelings of emasculation. In essence, she seems as much to blame for it as does his shrinking.

This is made even clearer when we consider their relationship prior to the onset of Carey’s condition. It is revealed that Louise has been a “security bug,” worried about her husband’s ability to provide, badgering him to relocate to the East Coast where he can work for his older brother. In this way, Carey has already been made to feel diminutive before beginning to shrink physically. Thus placed in a subordinate position as “little” brother, Carey has already been at least partially emasculated by his wife before the narrative begins; their daughter, an only child, symbolizes the “one mating act” after which the black widow attempts the destruction of her mate. His feelings of inadequacy and the tensions between the couple only escalate when Louise’s fears are realized and Carey is no longer able to hold a job, thus adding one more layer of distance between them; in addition to being unable to perform sexually with his wife or even arouse her, Carey is made to feel like less of a man because he cannot provide for his family. It should be noted that the equation of masculinity with providing is not strictly Louise’s; Carey buys into it as well, defining his subject position according to the dominant ideology. Still, his shift away from the breadwinner role, her domination of him, and his size, cast him as victim.

Other elements of misogyny in the text can be seen in the character of a pedophile who gives Carey a ride, mistaking him for a boy whom he hopes to seduce. Describing a friend who has gotten married, the would-be molester says, “And what was a man became a creature of degradation, a lackey, a serf, an automaton. A—in short—lost and shriveled soul. . . Women. Append them to cancer. They destroy as secretly, as effectively, as hideously.” Such an assessment suggests the black widow’s destruction of its mate as well as Louise’s apparent culpability for her husband’s emasculation. While Carey’s consistent attraction to women and desire for female companionship indicate a rejection of the pedophile’s philosophy, the degree to which he defines himself strictly in terms of sexual ability and desirability reveals that he may be operating under a similar mindset. That is, when women reject or belittle him, or even fail to find him attractive or consider him virile, his defining sense of masculinity is degraded, shriveled, and destroyed. His self-conscious and pathetic attempt at a relationship with the doll suggests a degree of objectification in his view of women, further suggesting misogynistic feelings below the surface of his seeming appreciation of female beauty.

Carey’s misogyny is most clearly revealed, however, during the long sequence in which he lusts over his daughter’s sixteen-year-old babysitter, Catherine. Having shrunk to twenty-one inches and no longer able to hold a job or care for his daughter, Carey submits to the humiliation (in his view) of hiding in the basement while his wife goes to work and Catherine watches their daughter. He begins to fantasize about Catherine even before seeing her, imagining her as seductive and worldly; his disappointment at finding her pudgy and uncouth does not temper his desire, and he finds himself unable to stop watching from a window as she sunbathes or sneaking around the house to peak at her drying off after a shower. Carey attempts to rationalize lusting after a minor by using the same logic he will later use to justify his dalliance with Clarice, telling himself he feels this way “because she is so much smaller than Lou.” Rationalized or not, his thoughts mirror those of the pedophile, as do his thoughts about women in general. After Catherine snoops around in the basement where Carey hides from her, he goes on a tirade: “Nosy bitch! You couldn’t trust one of them.” Furthermore, his objectification of women that will later manifest itself in the doll makes an uglier showing as he spies on Catherine, confusing his fantasy version for the real thing and then discarding her subjectivity altogether as he asks himself, “What was she doing? What was the pretty girl doing? Not pretty—ugly. What was the ugly girl doing? Who cared whether she was pretty or ugly? What was the girl doing?” It is her gender that interests him, not her individual qualities. As a female, she has the potential to satisfy his needs, to bolster his slipping sense of masculinity, and his interest in her does not go beyond this utility.

To the degree that women have the ability to affirm or deny Carey’s masculinity simply by providing or denying a sexual outlet, one could argue that women in this text have the real power; however, in the world of this novel, that power is malevolent and takes its ultimate form in the black widow, a creature that ties sex to death (mirroring the pedophile’s argument), and just as Louise has symbolically done by seeming to question Carey’s manhood before and after he begins to shrink. For Carey, the black widow is “more than a spider. It was every unknown terror in the world fused into wriggling, poison-jawed horror. It was every anxiety, insecurity, and fear in his life given a hideous, night-black form.” When Carey decides to use what he assumes to be his remaining two days of life to hunt and kill the spider rather than simply let the two days pass or hasten his end by killing himself, it is an attempt to wrest some of that power from the malevolent force and to affirm his masculinity not only by destroying this symbol of malevolence and insecurity but by engaging in the next best thing to sex for the insecure male—Carey gives himself a job to do.

It is a strategy he has employed previously. After regaining a measure of his manhood by sleeping with Clarice but aware that it was only a temporary solution to his problem, he had turned his energy and anxiety away from sex and toward work, writing a manuscript to chronicle his ordeal and soliciting publishers. Upon its acceptance, Louise’s anxieties over security were quelled, and she offered him a different affirmation of his status, telling him, “You’re still the man I married.” Now, hunting the spider becomes a task with similar ramifications. On his journey toward the spider’s territory, he begins thinking of his wife and daughter and the simple pleasures of being outdoors but pushes these thoughts from his mind, for they distract him from his purpose: “They were not part of his life now, and it was a senseless man who dwelt on things that were not a part of his life. Yes, he was still a man. Two-sevenths of an inch tall and still a man.” In his eventual triumph over the spider, Carey thus affirms his masculinity not only by ridding himself of the embodiment of all his fears and insecurities, emasculation among them, but also by completing a task that involved cunning, planning, daring and brute strength. This is not mere masculinity but rather a type of hyper-masculinity not unlike that which compelled him to want to be the sole breadwinner in his former life, a masculinity that drove him to define his identity by sexual performance and desirability rather than compatibility, compassion or other less “manly” traits, a masculinity that has revealed itself to be terribly fragile and easily lost along with jobs and stature.

Interestingly, Carey finds himself utterly at peace after killing the spider. In a literal sense, he can sleep in peace knowing the spider will not be hunting him. But he also experiences a more philosophical kind of peace in the last few chapters, finally giving up on his hope of being able to contact Louise and let her know he is still alive, if only for one more day. On what he assumes will be his last night—he is now one-seventh of an inch tall—he realizes that he has lost hope but not contentment. He is ultimately proud of himself for feeling contentment in spite of his impending death: “Yet he could smile. At a point without hope he had found contentment. He knew he had tried and there was nothing to be sorry for. And this was complete victory, because it was a victory over himself.” That is, the hyper-masculine version of Carey has defeated the emasculated, insecure, suicidal version. He is furthermore content because he is alone, because he has given up hope of contacting his wife and those vestiges of his former life in which he had been threatened with emasculation: “This, he knew, was courage, the truest, ultimate courage, because there was no one here to sympathize or praise him for it.” He ends the night bellowing “at the universe, ‘I’ve fought a good fight!’” but adds “under his breath . . . ‘God damn it to hell.’” For all its affirmation of masculinity, this self-consciously macho epithet is undercut by the fact that it is whispered rather than shouted, suggesting that there may still be something holding him back, intimidating and stifling him.

That Carey ultimately survives after his night at one-seventh of an inch, discovering undreamed of possibilities in his continued journey into the infinitesimal, suggests a middle ground, an alternative to the linear either/or thinking that he has used to define his world, himself and his masculinity. However, in the sense that the discovery comes only after he has stripped himself of all attachments and of everything that made him a man for better or worse, the text suggests that such a middle ground cannot be negotiated in any other way. A wife, a child, a house, a job, the need to provide, the need to be desired and affirmed as a dominant sexual being—all of these things, the text indicates, keep a good man down, prevent him from reaching his potential, blind him to the possibilities around him. And it is only upon gaining his complete freedom from these signifiers of masculinity that Carey finds the freedom to “run into his new world, searching.”

Philip Dick Richard Matheson science fiction novel Scott Carey The Shrinking Man