But What’s My Motivation?

I’ve been a bit quiet for the last couple of weeks: Christmas stuff, a shift in my schedule, and trying to finish the first draft of my follow-up to Dead Man’s Hand are all taking time away from blogging (and other things I should be doing).

I ran into a little problem about halfway through the novella I’m drafting: the character’s motivation seemed lacking. He’s a lawyer who specializes in working with the undead and paranormal, and he’s hired by a ghost who needs help getting her descendants out of the house she’s haunting. A little ways into the book, I realized there wasn’t much in the story to motivate the main character’s actions–just a paycheck. In the real world, getting paid is enough motivation for most of us to do things like roll out of bed in the morning and face traffic with a commuter mug in one hand and a steering wheel in the other. But in fiction…there needs to be more.

It’s a problem I’ve dealt with before. When I had the idea for the book that became Strictly Analog and pitched it to the agent I had at the time, her critique came back saying that the book sounded like a boring detective story, that the character’s motivation wasn’t clear. Motivation? I thought. Well, his motivation is for justice. People have done bad things, and he wants to set it right. What more motivation does he need?

The thing is, that might have worked for Raymond Chandler 70 years ago when he was writing his Philip Marlowe books, but it doesn’t work as well today. Marlowe is an awesome character, but we don’t get to know much about him. He’s been compared to a knight who’s on a quest for answers and justice and will stop at nothing–not even if it endangers him personally–to reach his goal. It’s not unusual for him to find resolution in the case he’s been hired for, only to continue digging once his “job” is over because there’s something more to it, some other crime or cheat or deception that the other characters aren’t even aware of but that Marlowe has discovered through his investigation. So he pushes on just for his own satisfaction, not because it’s his job.

This high-minded idealism was what I envisioned for Ted Lomax, the protagonist of Strictly Analog, and I was annoyed at the agent for not seeing it that way. But then I had to stop and think. I’m obviously not Raymond Chandler, and to make those comparisons, even loosely, was taking me down the wrong road.

Heck, Chandler himself might not be able to get The Big Sleep published in today’s market.

Then I thought of another detective–Easy Rawlins in Walter Mosley’s Devil in a Blue Dress. Rawlins has some shenanigans he needs to get to the bottom of, but he also has a bigger motivation: he needs to get paid so he can keep his house, his little piece of the California Dream.

After that, things began clicking with my book. Sub-plots began forming. The main character gained a slightly estranged daughter, and the daughter got herself into a bind, which accounted for the main character acting the way he did to solve the big case–sometimes at great personal risk. Just like Marlowe, only a bit less existentially, a bit easier for readers to connect with.

So here I am a couple years later with another character lacking motivation. I’ve already worked it out, but it’s funny to me that I keep needing to learn the same lesson over and over.

Here are a few things to think about in developing a character’s motivation:

1. Dreams Deferred. What does the character want but has failed to achieve? It could be a goal or a dream or the fulfillment of a simpler need. It can be especially helpful if the character is in denial about the very existence of this goal but rediscovers it as the plot rolls along. This moment of realization can be an epiphany for the character and for readers.

2. The Fear of Letting Go. What is the character afraid of losing? A character might be quite comfortable as a story begins, but is aware that the status quo depends on something like a job or marital stability or the success of a rebel alliance. So when that thing is threatened or (maybe temporarily) done away with, the character is set adrift and, after some struggling, becomes motivated to get the thing back, maybe in a new form.

3. Other Fears. What else does the character fear? Death? Failure? Unemployment? Being forgotten or unloved? As the character’s fears reveal themselves and threaten to come true, these things can push the character to act.

4. Sex (and love, of course). If a character’s motivation is simply to get laid, and you’re not an aspiring porn writer, then you need more (check 1-3 above or 5-6 below), but if there’s more to it, sex and relationships can be a huge motivator: either to save a relationship that the character feels defined by, or to start such a relationship. Along the same lines, characters can struggle with sexual identity or fulfillment or adequacy and be motivated to behave in a variety of ways accordingly.

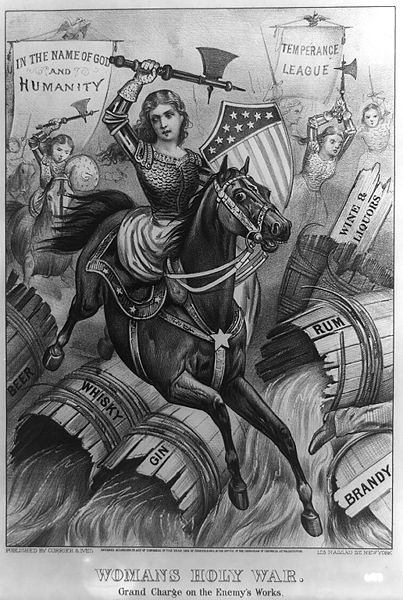

5. Morals and Values. Some characters are largely defined by the things they value. Look at Ned Stark in Game of Thrones, for example, and the way he’s driven by his sense of honor. If a character has religious convictions or is grounded in a particular political view (empire vs. rebel alliance, say), then those positions may inform the character’s thoughts and actions and propel the character forward.

5. Morals and Values. Some characters are largely defined by the things they value. Look at Ned Stark in Game of Thrones, for example, and the way he’s driven by his sense of honor. If a character has religious convictions or is grounded in a particular political view (empire vs. rebel alliance, say), then those positions may inform the character’s thoughts and actions and propel the character forward.

6. Revenge. This is a good one and can easily be linked with any of the above. If the thing (or person) that had previously motivated and defined the character is taken away–either by powerful forces or through betrayal–the character may be motivated to start kicking ass to set things right.

There are more, of course, and it may be especially useful to mix and match or to have conflicting motivations to add layers to the narrative and development. What sorts of things motivate your favorite characters?

Dead Man's Hand Devil in a Blue Dress Easy Rawlins Game of Thrones Humphrey Bogart literature Motivation Ned Stark Philip Marlowe Raymond Chandler Strictly Analog The Big Sleep Walter Mosley Writing

3 Responses

I have been surprised by what some of my friends who are lawyers have been willing to do for a paycheck, but I agree that such a motivation usually isn’t enough for fiction without higher stakes involved. I read Erin Morgenstern’s historical fantasy “The Night Circus” recently, and I kept asking myself what the motivations were behind the characters’ actions. A lack of motivation (and a lack of plot), however, didn’t keep that book from getting published and from being a bestseller. It’s an “atmosphere” book, I guess. Perhaps certain genres tolerate lower or nonexistent motivation/stakes.

I just finished watching all of Joss Whedon’s “Firefly” + the film “Serenity” in just a few days of obsessively clicking the “next” button. I’d say the writing on that show is the best there is. Captain Malcom Reynolds is one of the great anti-heroes of Sci-Fi history and could easily be a poster boy for multiple motivations grounded by the main identity theme of rebel who lost the war fighting against an evil empire.

In print I am thinking of Katherine Dunn’s “Geek Love” and trying to recall the motivations of various characters. Olympia Binewski is the patron saint of freaks and outcasts. (slight spoilers) Her repressed fury with her secret daughter for wanting to get an operation to remove her one minor deformity is an amazing affirmation, in line with the entire purpose of this bizarre, disturbing book : being unique and unusual should be prized above conformity. Oly is motivated by blind love for a villain and a wish to be more unique, like her brothers and sisters, instead of just an ordinary albino dwarf.

[…] ← But What’s My Motivation? January 14, 2013 · 6:24 am ↓ Jump to Comments […]

Comments are closed.