Science Fiction: The Cockroach of Literature

While capitalizing on a cute phrase he stumbled upon, Robert McCrum at The Guardian has come up with a list of literary genres. Since this is coming from a UK perspective, it’s not surprising that he would have a very different set of genres than an American critic would have. On this side of the pond, genre writing has been a force to reckon with for a long, long time. Most Americans would include detective fiction/mysteries, westerns, and horror, as well as African-American, Chicana/o, Asian-American, GLBT, and so on in a list of genre fiction where McCrum includes things like Australian lit, commonwealth lit, etc.–the kind of thing American critics and readers would likely think of as “world” or maybe multicultural literature.

That’s okay, and really it’s kind of refreshing to be reminded that readers from different cultures have different perspectives on things such as literary genre.

There are a few places where the author gets off track–as when he points out that Fifty Shades of Grey is “quintessential” erotic lit. Not that I’m a big reader of the genre, but my guess is there’s probably something out there that’s been around a lot longer and is far more “quintessential” than this current crop of mommy porn.

But where I really had to stop was when McCrum got to science fiction/fantasy (bad enough that he lumped them together, but whatever). He refers to this genre as “the cockroach in the house of books: it survives on scraps and never goes away.” He then singles out H.G. Wells and J.G. Ballard (both British!) as SF/F authors whose works have reached the level of the “sublime” while hinting that this is very unusual for the genre.

My first response is sort of a literary version of “Oh no he didn’t!” I want to jump to SF’s defense and rattle off a list of authors–some of them not even British–whose speculative works have hit the sublimity benchmark. Some will disagree with it, but here’s my shortlist: Philip Dick, Alfred Bester, Ray Bradbury, Connie Willis, Kurt Vonnegut, Harlan Ellison, William Gibson…I have to stop before the shortlist isn’t short any more. Any SF fan reading this has his or her own list, I know. And I’d probably agree with most of them.

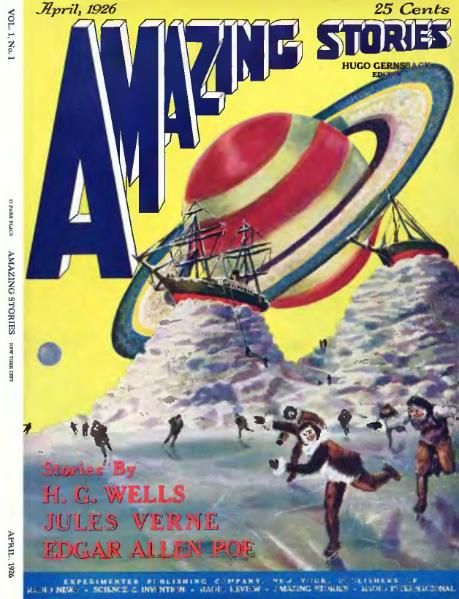

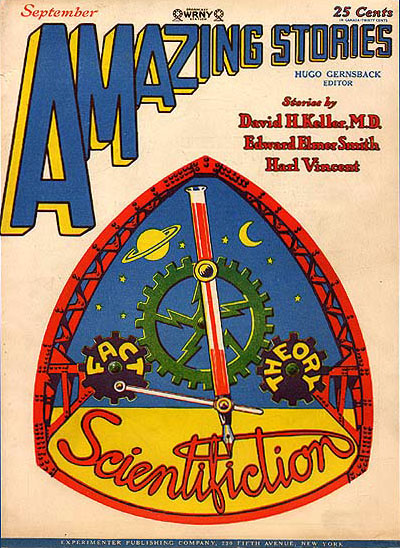

After taking a deep breath, though, I remind myself that this dismissive view of SF is nothing new. I suppose we could blame the ghettoization on Hugo Gernsback. Before he started publishing Amazing Stories in 1926, science fiction wasn’t clearly defined. Capital W writers of Capital L literature had been exploring questions about science for a long time before that–people like Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Jack London, E.M. Forster and others–and back then, it wasn’t looked down upon as kids’ stuff. Before the age of pulp fiction, they weren’t even calling it science fiction. It was fiction about science, scientific romance, scientific fiction (and let’s not forget Gernsback’s run at the term “scientifiction” as he tried to define the genre).

But when Amazing Stories hit the stands, and its imitators followed, a whole new crop of writers began exploring questions of science, developing tropes that each built off of in their fiction. Is that what it means to be a cockroach? Probably not according to McCrum’s definition. These writers weren’t stealing scraps from the literary table; they were borrowing from and building off one another, so that science fiction soon began to be about space exploration and aliens, an exciting future that reflected authors’ excitement and/or worry about their present.

At the same time, science fiction began to be looked at as separate from those more respected Capital L literary explorations of time and space. Even so, other writers like Orwell and Huxley kept writing literary SF and got considerable respect for doing so. Can we say that Huxley was a cockroach for taking “brave new world” from Shakespeare? More recently, respected writers like Margaret Atwood and Michael Chabon have written science fiction. You won’t find it on the SF shelves at B&N, though. It’s in the Capital L literature section while anything with a dragon or a space ship or an alien on the cover is over on those shelves near the graphic novels. You know those shelves, the ones where the cockroaches hang out waiting for crumbs.

The genre has been in the literary ghetto for a long time and has survived quite nicely, and maybe–as a result–should wear its cockroach badge proudly. I don’t agree with McCrum when he says that SF lives off the scraps of other genres, but science fiction is for the most part as unstoppable as those nasty little bugs that cling to the corners and crevices and come out at night to feast. The metaphor doesn’t work when you consider that SF doesn’t scatter when you turn the lights on, but still SF writers are a tenacious bunch.

Upon further reflection, I can say it doesn’t bother me. If e-books and on-demand publishing and indie authorship are somehow bringing about a metaphoric apocalypse in publishing, I don’t mind being one of the cockroaches who’ll be left behind to start a brave new world.

Oops. I guess I’m a cockroach, too. Sorry, Shakespeare.

Aldous Huxley Amazing Stories books E.M. Forster George Orwell Hugo Gernsback Jack London literature Margaret Atwood Michael Chabon Nathaniel Hawthorne pulp fiction Reading Science Fiction science fiction novel traditional science fiction Writing