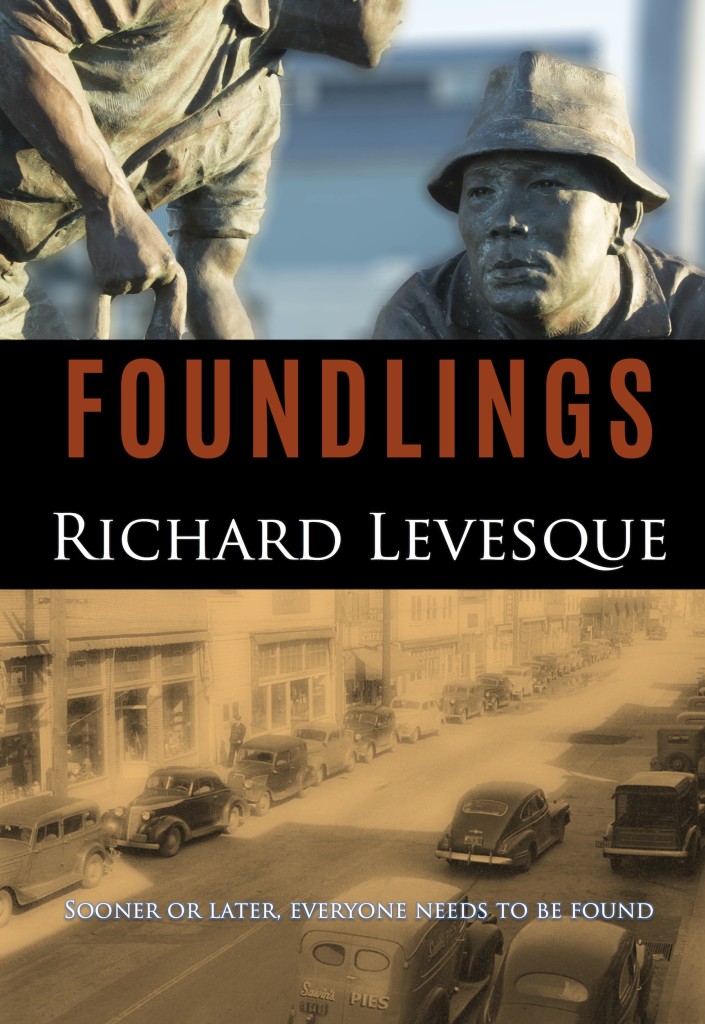

Sooner or Later, Everyone Needs to Be Found

Thank you for visiting the free preview page for my novel, Foundlings. Below, you’ll find the first chapter of the book. Thanks for checking it out!

Chapter One

Furusato, April 1925

For what must have been the hundredth time that year, Masaru Nakamura cringed at the creaking of the door as he pushed it shut behind him and stood on the landing outside his home. The door squeaked loudly enough to wake all of Tuna Street, and it was a wonder that it hadn’t yet. Only when he had closed the door did he let himself exhale, not realizing until then that he had held his breath while the hinges cried out. He supposed the door groaned just as loudly throughout the day, but he seemed to notice it only in the mornings when he stepped outside to greet the day and Furusato hadn’t yet come to life. Later, the creak would be drowned out by the rumbles from the canneries, the cars rolling past, and all the rest of the noise that made up life on Tuna Street. What was more, he knew, some distraction or other would occupy his mind throughout the rest of the day; every other time he pulled this door open or shut, he’d be too busy thinking of some pressing matter to even notice the hinge in want of attention.

As it had for the last several mornings, a thick fog lay upon Furusato, no doubt covering all of Terminal Island, the rest of the harbor, and reaching inland past San Pedro and Long Beach. He waited for the lowing of the foghorn, and when it had sounded, he put a hand on the wooden rail, almost spongy from the moist sea air that wormed its way into the village every morning, and started down the stairs that hugged the outside of his building.

That was how he thought of it: his building. The bank really owned it, but it felt like his nonetheless. His name was on the sign above the first floor grocery store—Nakamura Market—and his family still slept in the home upstairs. Three small bedrooms with three children and his wife, Mai, who’d all soon be up eating and preparing for school before coming downstairs to do what they could to help him get ready for the day’s commerce. He was expecting two deliveries this morning and needed to make the shelves in his storeroom ready before the first customers came in.

At the bottom of the stairs, he stopped and stretched, looking up and down Tuna Street for a moment. A few shadowy figures moved in the fog—other merchants getting ready for their days, or maybe a few of the women heading already toward the canneries. Most of the men in the village spent their days on the water, out in their boats until the holds were filled and they brought their catches into town. The men who owned or crewed the boats would already be out, up before the sun and cutting through the waves beyond the breakwater, maybe even past the fogbank.

Masaru frowned at the sound of a cat’s squall, probably a tom squaring off with another and ready to fight over a female or a fish head. In a few seconds, the fur would start flying and the screeches would finish the job his squeaky door had started, waking everyone in the houses nearby—the Fujimoras to the left, the Watanabes to the right, Dr. Yamamoto in the house across the street, his home doubling as his office on the second floor above Hanamura’s Hardware. Scanning left and right, Masaru caught no sign of the offending cat, but his eyes did light on something unusual. A wooden milk crate sat before the screen door leading into his market.

His frown turned into a scowl. He was not expecting any deliveries, and if he had been, no driver would have simply left a crate at his door and driven off in the night. Fearing a prank from neighborhood boys, he approached the crate, noting that it was old, the blue paint mostly worn from its sides. And then he realized that the tomcat’s low growl was coming from the box, and he swore under his breath. What have those damned kids done now? he thought, imagining a cat stuffed inside a pillowcase and ready to tear the hell out of anyone kind enough to let it out.

But the box did not contain a cat. And the noise he’d been hearing was not a growl. At first, all he saw was a rumpled blanket, but when he poked at it with one thick finger and the yowling stopped, he pulled at the blanket’s edge to find a little baby looking up at him.

Now he swore out loud, “Kuso!” Frozen to the spot for only a second, he charged back into the middle of the street, scanning up and down into the fog for any sign of who had left the baby and the box at his door. There was nothing, no one. After another quick, uncertain glance at the box, he darted to the far corner of the building, hoping he would see someone hiding there, watching him and having a good joke. But still there was no one. Another glance across the street told him no one was hiding in the space between Hanamura’s Hardware and the house it bordered.

The baby cried again. No, no, no! he thought. This couldn’t be happening. And yet he knew it was, knew that this was no dream; the fog might fade like a nightmare when the sun burned through as it rose, but the baby and the worn milk crate and his feelings of panic and disbelief were here to stay.

He rushed back to the box and squatted next to it. “Don’t cry,” he whispered and made a cooing sound that had always calmed his daughter, Minato. But Minato had been born four years ago, his third child, and Masaru was thus almost four years out of practice in his cooing. It had been Mai who’d mostly dealt with their three children in infancy, and he hesitated to touch the baby, fearful he would do something to harm or frighten it without meaning to.

But the crying was getting louder, so he tugged at the edge of the blanket and found the baby’s tiny hand. “Shhhh, baby,” he whispered. “Enough crying. We’ll find your mama now, all right?”

The baby gripped his finger and stopped crying for the moment. Masaru smiled at it. “Good baby,” he said.

It looked so little in the box. Masaru tried to remember how his children had looked as babies, wondering just how new this little one was. So tiny, he thought. Who would do this to you? More confounding was the fact that the baby was not Japanese. Between two and three thousand people lived in the fishing village on Terminal Island, and only two or three were white, the rest all Issei or Nisei, the first and second generations of Japanese immigrants. How a little gaijin baby could end up here on an island of Japanese fishermen—let alone in a box in front of his store—was more than Masaru could begin to fathom.

Resting one knee on the ground, he tried to decide what to do next. He could take the baby upstairs and wake Mai, but he immediately pictured the chaos of his three children crowding around, poking at the baby, all talking at once with Mai trying to shush them and the baby getting more upset. Masaru would end up yelling. Minato would run from the room in tears. Her brother Taichi, two years older, would leave in a sulk. And Naoki, the eldest, would give his father a stoic look, trying to be a man. Mai would just scowl before turning her attention back to the baby, and Masaru would be left to shrug and wonder how his day had gone so bad so quickly.

The baby moved in its blanket, and Masaru caught the crinkling sound of paper. Feeling around the edges of the box, he found a folded piece of yellow stationery bordered with irises. With a resigned sigh, he unfolded it and stared at the English script, elegant letters that meant nothing to him. “Kuso,” he said again, shit.

He didn’t need to go upstairs and stir his family to make the day go badly; the damage was done.

Getting off his knee, he dropped the note onto the blanket and then lifted the box, baby and all.

“Are you a boy or a girl?” he said, not wanting to do any investigating to find out. The baby was so little that it was hard to tell just from its face. Women seemed able to discern such differences just from seeing babies in their swaddling, but it was all a mystery to Masaru. He’d never felt much reason to enlighten himself.

“All right, then,” he said and started back toward the stairs. Naoki would be able to read the note once the chaos died down.

But with his foot already on the bottom step, he stopped and turned, looking up at the building across the street. Dr. Yamamoto’s name was painted on the window above the hardware store, gold letters outlined in black, all of them starting to chip away.

“Yamamoto reads English,” he said to the baby. “Maybe he’ll know what to do with you.” He turned away from the stairs to cross the street. Maybe he’ll even take you off my hands, he thought, feeling a bit less burdened already.

The milk crate was ungainly, and he hesitated a moment as he started up the wooden stairs to Yamamoto’s. Maybe it would be better, he thought, to leave the box at the street and carry the baby up in the blanket. But it might be easier, Masaru knew, to leave the baby with the doctor if it was still all tucked in its box. Careful to keep his balance with the crate held out in front of him, he let himself imagine the possibility of just leaving the box at the top of the steps for the doctor to find when he opened for business. Even as he pictured it, he let the image slip away. There were some things he could not live with. Abandoning an already abandoned baby was one of them.

At the top of the stairs, he set the box on the landing and then knocked at the doctor’s door. He listened, hearing nothing but the baby’s little grunts and the distant foghorn’s moan. He knocked again, harder this time.

He heard footsteps and then the doctor’s voice, muffled through the door and gruff. “Is someone dying?” Yamamoto asked.

“No,” said Masaru.

“Then come back at nine o’clock when I’m open.”

More footsteps, retreating.

“No one’s dying,” Masaru said a bit more loudly. “But someone’s been born.”

“Eh?” he heard the doctor say.

“There’s a baby.”

A lot of doors stuck and swelled in the moist air of Furusato, and the doctor’s was no different; the knob turned and there was a moment’s pause before it pulled free of the jamb. Then Dr. Yamamoto was standing there in striped pajamas, his face a craggy map of wrinkles and the whiskers in his graying mustache pushed in all directions from having been slept on and not combed. The doctor held the doorknob with one hand while the other fumbled with wire-rimmed glasses. “Takeshi’s wife had her baby?” he said, incredulous. “Too soon.”

Then he focused on Masaru and took in the milk crate at his feet. He didn’t need his glasses to see what his neighbor was presenting him with.

“Where’s the mother?” he asked.

Masaru shrugged. “It was down there.” He turned his head toward the street and tipped his chin downward. “At the door to my store.”

The doctor let out a long sigh. He seemed, Masaru thought, to be assessing how much trouble this was going to bring. Masaru hoped his pleading look would outweigh any worries the doctor might have.

“Come in then,” Yamamoto said, standing aside.

He closed the door with a push of his shoulder once Masaru was inside. Then he led the way through the sitting room into the examination room at the back of the building. “Set it there,” the doctor said, pointing to the raised table where he saw all his patients. There was a basin in the corner, and Yamamoto quickly washed and dried his hands after he had turned on the lights.

The baby cooed as Masaru stood over it, his finger back in the baby’s grip until the doctor approached. Then he stepped back and let Yamamoto go to work. In a few seconds, the baby and blanket were out of the crate, and the doctor was unbuttoning the little outfit the infant wore. The diaper underneath was wet, and when the doctor removed the pins and pulled the cloth away from the baby’s skin, Masaru saw that it was a boy.

“Congratulations,” Yamamoto said, a facetious smile playing across his face.

Masaru wanted to protest but saw that the doctor was joking and so kept his mouth shut.

“He looks healthy,” the doctor went on. “Maybe…two or three weeks old. Not Japanese.”

“That I could tell.”

“Mmm,” the doctor grunted, still looking at the infant.

Masaru reached into the crate and held the note out to Yamamoto. “This was in there with him.” The doctor glanced at the folded paper but made no move to take it from him. “It’s English,” Masaru went on. “I need you to read it.”

Yamamoto looked back at the boy, ignoring his request. “Wait here,” he said. Then he left the room.

Masaru did as he was told, watching the naked baby, who moved his arms and feet but not with anything that resembled purpose. “What are we going to do with you, little boy?” he asked.

Dr. Yamamoto returned after a few minutes and set two diapers and a small glass bottle with two rubber nipples on the table. “I don’t have any formula. Do you carry any in your store?”

Dumbfounded, Masaru just stared. Then he shook his head, no.

“Maybe another storekeeper, then. I can make some phone calls.”

“All right,” Masaru said, unsure. Then he added, “The note?”

“Huh?” Yamamoto looked surprised. He saw the note in Masaru’s hand now, as though noticing it for the first time.

“It’s in English,” Masaru said again.

The doctor said nothing, just reached for the folded letter.

Yamamoto adjusted his glasses a bit, and then Masaru watched as the doctor scanned the sheet of paper. Half a minute later, he sighed and began reading the letter again, this time out loud in Japanese, pausing now and then to process the English before continuing.

“Please take care of my baby,” he said. “His father and I are not married. He wants nothing to do with our son, and my family will disown me if I come back to them with a baby. I do not know what else to do. I know you will be a kind father. I saw you once with your children. They all seem so happy. If I take my baby to an orphanage, I will never know if he is safe or loved. If I leave him with you, I can be sure he is in good hands. If you cannot keep my baby and raise him as your own, please, I beg you, find another family that you know well who will give him a good life. When he is old enough, tell him that I loved him and miss him and that it breaks my heart to give him up.”

Yamamoto set the letter on the examining table and stared at Masaru, who stared back without seeing.

I saw you once with your children. The words echoed. The all seem so happy.

“Who is she?” the doctor asked.

Masaru shook his head. “I don’t know. I can’t begin to…”

He encountered so few white women on the island and almost never took the ferry over to the mainland. How could this baby’s mother have seen him and his children? Where?

The thought of the ferry brought the memory back in a rush of images. It couldn’t have been more than two months ago. A young couple had come over on the ferry, driving their Ford around Fish Harbor for a laugh, it had seemed. They had gone up and down Tuna Street, down to what the gaijin had called Brighton Beach before the fishing industry had turned the rich folks’ playground into canneries and company housing. It had been a Saturday; Masaru remembered because his children were not in school, and he’d put them to work in the store sweeping and stocking shelves. When they had finished their work, Naoki had begged Masaru to go outside with them to play catch in the street. Playing with his children was not something he did often; there never seemed to be time. But that day, Masaru had said yes.

They had been tossing a baseball outside, he and his three children, when the Ford came back down Tuna Street one more time, and as the car approached Nakamura Market, it had blown a hose or a fan belt—Masaru did not remember exactly what the problem had been. All he recalled was the car rolling to a halt in the middle of the street in front of his store. The driver got out and cursed, kicking a tire before pulling up the hood to look at the engine. He was young and looked like he had a temper. He left the driver’s door open, affording Masaru a glimpse at his companion. She was young like the driver and pretty from what he’d been able to tell, with short hair, as was the fashion among the white girls, and a large belly. She had smiled at him, embarrassed he thought, and he had smiled back, not sure what else to do. He realized now that Naoki, Taichi, and Minato had all been lined up behind him, probably with big smiles on their faces as they’d watched the spectacle of the broken car and its angry driver.

They all seem so happy.

He could not remember how the incident had ended. Probably, he had ushered the children back inside while the young father-to-be found a few people to help push his car to the Fish Harbor service station. Or maybe the man—Masaru had assumed he was the husband—had gotten a spare part from Hanamaru’s store and driven off with his pregnant wife—who was not really a wife and on whom the Nakamura family had made a strong, unintended impression.

Masaru described the incident to Yamamoto. “Do you remember that happening? Did you notice them?” he asked.

The doctor shook his head and began diapering the baby.

“What do I do?”

Yamamoto finished fastening a pin and looked up. He raised an eyebrow. “It looks like you have a new son.”

It was not the answer Masaru wanted to hear. “Should we call the police? Isn’t it a crime in America to abandon a child so young?”

Yamamoto shrugged. “Maybe. But they’ll never find the mother unless she turns herself in.”

“What would happen to the boy?”

“The police will probably take him to a hospital first, have another doctor look at him. Then…” He shrugged again and went back to getting the baby into his clothes before adding, “An orphanage most likely. Just what the mother didn’t want.”

“Are they such terrible places?”

“I don’t know about American orphanages. But I expect it would be a place with a lot of children and not much love. If you ask me, he’s better off with you—with a father, not an administrator. But…” He held the baby up now, fully dressed again, and for the first time smiled at the boy, and said, “There’s no law that says you have to take care of him just because his poor mother trusted you with the job.”

Crestfallen, Masaru nodded. He did not want the boy, did not want another mouth to feed. He wanted this morning not to have happened. He wanted to have been yelling at his children in the street rather than playing ball with them on the day of the broken-down Ford, anything that would have kept the Nakamuras from creating the picture of an ideal family for a woman without one.

“I don’t suppose,” he said quietly, “there’s any way you could take him. Eh?”

The doctor shook his head. “I’m too old, and I don’t have a wife to help me with him.”

He extended his arms across the table, holding the boy out to Masaru. His expression said, Take him, and Masaru did, uncomfortably folding the baby into his arms.

“It’s better this way,” Yamamoto said. “His mother had the right instinct. He’s a lucky boy.”

“Lucky,” Masaru said. He shook his head again to think of the corner he’d been forced into. A lucky day for the baby, maybe not so lucky for himself. Resignation in his voice, he said, “I suppose that’s his name then.”

“Kichiro?” the doctor said.

Masaru nodded. “Kichiro Nakamura.”

“Good.” Yamamoto nodded. Then he reached out to shake Masaru’s hand. “Congratulations. The easiest delivery I’ve ever done.” He smiled, his face a map of creases as a he looked at the baby in Masaru’s arms, and then Masaru watched as the smile faded into a look of concern.

“What is it?”

The doctor shook his head. “It’s nothing. For now.”

“Tell me. Is something wrong with him?”

Yamamoto sighed and crossed his arms. “No, he’s fine. It’s…the gaijin. On the mainland. Here in Fish Harbor, we do things as we please. Even adopting babies. But across the water…things work differently. You may not notice it when you go into Little Tokyo, but everything for the gaijin is paperwork and recordkeeping, signatures and approval. When I have to send my patients to the hospital…” He shook his head at the thought.

“I don’t understand,” Masaru said. “What does this have to do with…?” He looked down at the baby. It had started to squirm while the doctor spoke, so Masaru was bouncing it a little in his arms, unsure of what else to do.

“As I said, it’s nothing for now. But when it’s time for him to go to school, questions may be asked. Especially if his name is Kichiro Nakamura. A little white boy with that name is going to invite scrutiny. Think of a gaijin name for him, too. And a story to go along with it.”

Masaru had felt himself growing warm around his ears and across his forehead while the doctor spoke. If it was going to be this much trouble, maybe he should just give the baby away now, he told himself. But at the same time, he had already named the boy; Kichiro was his now.

“What kind of story?” he asked.

The doctor unfolded his arms, shrugged, and leaned against a cabinet. “Anything. Anything that doesn’t require paperwork. If you say he’s adopted and the wrong person gets curious, you may have someone from the county knocking at your door looking for paperwork.” He shook his head at the thought. “Say you’re taking care of him for a friend, a business associate. One of your suppliers in the city.” He drew away from the cabinet, getting excited as he talked, believing more and more in the fiction he was spinning even as the words left his mouth. “Say his father died and left the mother alone to run her fruit wholesale business. Maybe even died before the baby was born. It’s too hard for her. So she’s letting you take care of the boy until she can get her life back together again.”

“Why would she do that?”

“She has no other family.” The doctor pointed at the note framed in irises. “Like the real mother said, you’re good with children. She trusts you with her boy.”

Masaru nodded. The doctor’s fabrication didn’t sound unbelievable, at least in the short term. “It’s a good story. How long can it last, though? It won’t be believable forever.”

Yamamoto nodded. “In a couple of years, you can say she remarried and the new husband doesn’t want the dead husband’s boy around. But you never say you’ve adopted him. You just say you’re taking care of him for a while longer.”

“And the while longer never ends.”

“That’s it.”

Again, Masaru nodded. His glance shifted from the doctor’s uncharacteristically animated face, all crags and laugh lines, to Kichiro’s, all smooth and unmarked by care. “All right, then,” he said, hardly believing the words were coming out of his mouth. “I’ll get my children to think of a good American name that we can use if anyone asks.”

“Good,” said Yamamoto. He took off his glasses and wiped them on his shirt, repeating, “Good.”

Masaru left the milk crate in the doctor’s office and went back outside, the baby wrapped in the blanket. As he had known it would, the fog had begun to lift, and more people were out, mostly heading to the canneries. Soon the younger children would start walking to the East San Pedro School, and the older ones would head to the ferry to the upper grades across the bay. It would be hard to get his own children off to school this morning.

Let them be late, Masaru thought as he started up the stairs to his waiting family. When he opened the door at the landing, the hinges squeaked as loudly as they had when he’d first walked outside this morning. This time, though, Masaru did not notice.